IPOs and the increased maturity of private equity investing

In the second half of the twentieth century, the model for financing the growth of successful businesses became remarkably uniform.

A business would start out with an investment made by the founder(s), possibly supplemented by people in their network, and finance growth either through further investment from the founders or through borrowing from a financial institution (typically a bank). In the event the business reached sufficient scale, it would seek significant equity investment through listing on an established market.

This model has - thankfully - been disrupted in recent years.

Raising finance has arguably become easier than ever before

Firstly, it has become much easier for individuals to provide finance for unlisted businesses, either through peer 2 peer (P2P) lending or equity co-investment platforms.

Secondly, the scale of available private equity investment has increased hugely; although it may not compete with the capital available through a public listing, it can support an ambitious business further along its growth trajectory than it would have been able to in the past.

There are numerous high profile examples of this, with one of the most prominent being Twitter, the social network that raised over $0.75bn whilst remaining in private ownership.

What does this mean for Initial Public Offerings?

The most prominent manifestation of this change has been the shift in the position of the Initial Public Offering (IPO) in the model for financing growth.

It was historically a sunrise moment; a time when a business announced to the world that it had established a solid foundation and was ready to execute an ambitious plan for future growth.

Although a public listing may often have been the only viable source of equity investment at the required scale, there was also a prestige attached to the event that underlined a sense of the company ‘joining the big league’.

More recently, companies have delayed publicly listing. As described above, the ready availability of private equity capital has enabled companies to finance their growth plans without the need for an IPO.

It's hard to argue that an IPO isn't still a pivotal point in a company's existence, but it's not the sunrise moment it once was. In fact, it wouldn't be wrong to consider an IPO a sunset moment: a company will make an IPO when - and only when – it feels it has achieved scale and may achieve modest growth thereafter.

An IPO once you're at the top

The most comprehensive existing research into this trend comes from the USA. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) influential Investor Advisory Committee met on the 22nd June and considered a collection of reports into the declining number of IPOs.

Two quotes from one of the reports (authored by Prof Elisabeth de Fontenay) emphasise both the significance of the change:

“Rather than rushing toward an IPO, these companies are delaying going public for as long as they can… No longer the promised land for companies poised to grow, the public stock market is quickly becoming a holding pen for massive, sleepy corporations.”

And the radical change in the role of the IPO:

“Symptomatic of the diminished role of public capital raising is the recent phenomenon of companies going public long after they have achieved scale and primarily as a means for insiders to cash out, rather than to raise new capital for growth.”

This suggests that far from being the first opportunity to buy into a shiny new venture, the IPO has instead become a signal that a company is settled into a market and will shift its outlook towards consolidation.

In this sense, the purpose of the IPO is not to raise capital in advance of growth, but instead to reward private investors for their commitment.

Interpreting the impact for investors

The conceptual change is very clear, but how should it be interpreted?

Historically, investing in listed companies offered greater liquidity and less risk; shares in more established businesses tended to be easier to sell and financial performance was less volatile. Investments in such companies were considered a more conservative option.

Although the liquidity offered by investments in publicly listed companies undeniably remains greater, as the profile of companies in private ownership expands to encompass those with more established trading history, the risk profile is reduced.

Understandably, the private equity industry is increasingly keen to capitalise on the opportunities presented by these developments.

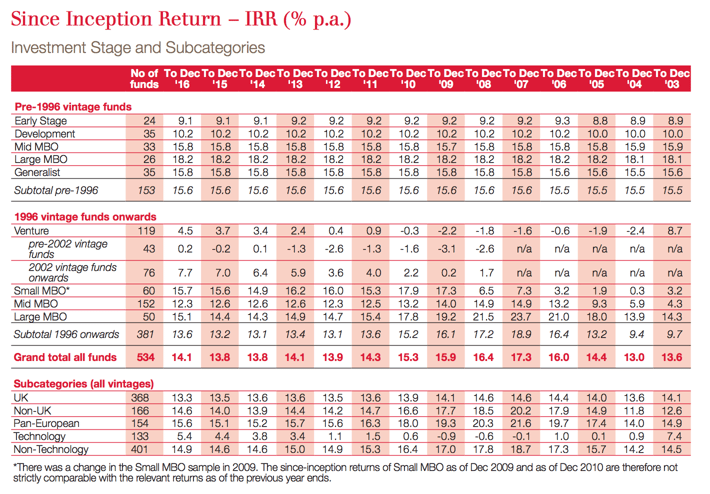

The British Venture Capital Association (BVCA) last week published its annual Performance Management Survey. It reported that private equity investments had delivered annual returns that outperformed the FTSE All-Share over three-, five-, and ten-year time horizons. It also reported that annual returns for private equity investments calculated on a ‘since-inception’ basis exhibit remarkable stability - within 0.3 points of 14% per year since 2011.

In an article for Spear’s, Bill Nixon – Managing Partner at Maven Capital Partners – confirms that High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs) have increased the average portfolio allocation invested through private equity by more than half. This reinforces the importance of equity co-investment platforms as a source of current and future investment opportunities for institutional private equity investors.

As an equity co-investment platform, GrowthFunders is happy to engage a wide range of investors – retail, professional, and institutional – to invest alongside one another in companies that exhibit high-growth potential.

We truly believe that the combination of more consistent, stable investment returns offered by unlisted companies and technology that facilitates co-investment across different investor groups is completely and utterly compelling.

%20(3)%20(2).jpg)